Pring-Wilson, convicted in stabbing after a fight, dies quietly in Colorado at 47 as electronics exec

Pizza Ring on Western Avenue in Cambridge

A former Harvard graduate student convicted in 2004 of stabbing an unarmed Cambridge teen to death after a night of drinking died in mid-August.

Alexander Pring-Wilson died in his native Colorado Springs, Colorado. He was 47, according to his obituary announcement. The cause of death is not listed.

In Cambridge, Pring-Wilson’s criminal case came to exemplify the city’s growing class divide coupled with the role that stereotyping and wealth can play in criminal justice.

The son of two attorneys and a member of the influential Pring family in Colorado, Pring-Wilson was a Harvard master’s candidate and an aspiring environmental attorney in 2003. After a night of drinking in Somerville and Cambridge, he was walking alone in the rain down Western Avenue after dancing at the (now closed) Western Front music club.

About 2 a.m., he crossed paths with Michael Colono, an 18-year-old Cambridgeport resident who was in the back seat of a cousin’s car parked outside the Pizza Ring while waiting for a food order.

Colono laughed at Pring-Wilson’s drunken stagger and after trading insults the two started fighting on the sidewalk. Colono suffered five wounds from a nearly 4-inch military-style knife that Pring-Wilson said he used for cutting carpet, according to court testimony.

One of the wounds sliced Colon’s right ventricle, pouring blood into the pericardial sac encompassing his heart. It would soon fill up, making it more difficult for the heart to beat and eventually stop, which it later did at Beth Israel Deaconess hospital.

Manslaughter conviction

Although character evidence isn’t allowed in self-defense cases, Pring-Wilson’s attorneys fed reporters unflattering details about Colono’s juvenile record while promoting Pring-Wilson’s credentials and likening him to Gandhi in open court. It worked.

In its coverage of his bail hearing in Cambridge, one Boston newspaper described Pring-Wilson as “strikingly handsome.”

The defense team also enlisted the polling company of future Donald Trump adviser Kellyanne Conway in an attempt to change the location of Pring-Wilson’s trial to a more favorable venue in Berkshire County, where they claimed residents would be more tolerant of a defendant who carried a knife. The tactic was unsuccessful, but Pring-Wilson’s lawyers endured.

Despite a manslaughter conviction in Middlesex Superior Court, Pring-Wilson would eventually serve just 15 months for the stabbing death. His conviction was appealed by a high-priced legal team, leading to a retrial, a deadlocked jury and a mistrial, resulting in a 2008 plea agreement.

After the criminal trial

Pring-Wilson never got his master’s from Harvard. Instead, he returned to Colorado, where he went by the name Sander Wilson, and worked for his stepfather’s electronics company, Low Voltage Wiring, which does mostly federal government and military business as LVW Electronics.

In 10 years, Pring-Wilson worked his way up in the company from business operations to the senior position of chief operating officer, according to his LinkedIn account.

In a civil suit, a Middlesex County Superior Court judge ruled that Pring-Wilson didn’t do enough to avoid the fight and a knife was more force than he needed to survive the altercation. His parents’ homeowner’s insurance policy later covered the $260,000 cost of wrongful death damages determined in the civil claim.

The Harvard Crimson covered Pring-Wilson’s arrest and ensuing judicial proceedings closely. But Harvard officials never acknowledged publicly his role in Colono’s death. The university’s official news outlet, The Harvard Gazette, didn’t report on the stabbing or Pring-Wilson’s trials.

He is survived by his wife, Janice Olmstead, and daughter Charlotte Alice Wilson, the obituary reads.

Six inches of rain pounded Lawrence on Tuesday morning, triggering flash flooding throughout the city and endangering lives, including that of a woman on Parker Street who was pulled from her vehicle by fire and rescue personnel.

The driver, who was alone, drove into a flood-prone area at Parker and Merrimack streets and panicked as water rose swiftly above her door, reaching a depth of between 4 and 5 feet, Lawrence Deputy Fire Chief Jack Meaney said.

The woman was transferred and treated by ambulance personnel, and was not believed to have needed additional treatment.

Lawrence fire and rescue safely removed a person from a flooded car at Center and Arlington streets, and assisted people at numerous homes where basements and yards flooded and water poured through roofs, the deputy chief said.

Fire personnel killed power at multiple locations to safeguard against electrical failures and fires.

All 24 on-duty personnel, along with the fire chief, deputy chief and two other department members, responded to some 60 alarms or emergencies between 9:30 a.m. and 1 p.m.

Response areas included Prospect Hill, Tower Hill, Jackson Street near Methuen, and Inman, Market, Berkeley and Sheridan streets as well as Winthrop Avenue and the Motor Vehicle Registry parking lot.

Emergency personnel were running from one call to another and hard-pressed to keep pace with the rash of emergencies, he said.

“We were spread pretty thin,” said Meaney, a 31-year veteran of the department.

Elsewhere in Lawrence, Merrimack Valley Transit relied on detours to maintain regular scheduled bus service, said General Manager Jesus Guillermo.

Local transit buses stopped briefly Tuesday morning from about 11:30 to 11:45 when intense rainfall flooded parts of the city, including Parker Street near the intersection with Merrimack Street, he said.

In North Andover, the owner of Jaime’s Restaurant, Jaime Faria, posted online that his High Street business sustained only minimal damage, but several neighboring businesses did not do as well.

The pond in the back of the East Mill flooded and water ran through the front of the mill, knocking out windows and doors, he said.

The severe weather flooded roads, stranded drivers and upset public transportation throughout the state. MBTA service was briefly disrupted by flooding in some areas of Boston, The Associated Press reported.

Locally, Lawrence was the hardest hit by the late-morning, early afternoon downpour. The city received 6.2 inches of rainfall; Tewksbury, 5.6 inches, and Andover, 4.4 inches, according to the National Weather Service.

In July, the Merrimack Valley was spared the flooding that plagued parts of Vermont, New Hampshire and farms in western Massachusetts, but the rain here was unusually heavy.

Between June 1 and July 22, Methuen received 15.89 inches or 112% more rain than the 30-year average for June and July.

Wild swings in precipitation, from brutally dry to wet, are the expected outcomes of climate change, according to UMass Lowell climate scientist Matt Barlow.

Barlow and a team of climate scientists have researched this weather effect in the Boston area, the propensity for pinballing between drought and flooding.

They published their findings in 2022 in a report titled “Climate Change Impacts and Projections for the Greater Boston Area.”

Hotter weather draws more moisture from the ground to the atmosphere, creating drought conditions, Barlow said.

For rain to occur, humidity at the upper levels must approach 100%, and the moisture needed to reach that threshold rises as the temperature rises. If the threshold is not reached, it is a humid day.

If the threshold is reached, with the additional moisture, there is more rain – a harder rain, he said. A warmer atmosphere can hold more water.

A NASA-led study published in the Water Journal in March and based on 20 years of satellite data confirmed that droughts and floods are more frequent, Barlow said.

“That is what we expect in a warming climate, that kind of whiplash,” he said.

Fourteen years after policing in Cambridge attracted national attention, the city’s two police departments are again considering improvements to how they interact with the general public amid calls for reform.

Attempts at change by the Cambridge and Harvard University police departments share similar traits, such as soliciting reviews from outside experts and appointing committees. They also operate under some very different parameters.

In 2009, the Cambridge Police Department came under scrutiny after Sgt. James Crowley arrested Harvard University professor Henry Louis “Skip” Gates Jr. on the porch of his university-owned house.

The incident and the reactions it drew provided a type of Rorschach test for race relations in America. It also prompted the appointment of a review committee and a 64-page report, “Missed Opportunities,” that answered few pertinent questions.

Cambridge officials announced in late February several measures designed to increase transparency and public safety. Meanwhile, the HUPD and its advisory board is preparing to update a previous activity report that drew fire when it revealed a disproportionate arrest rate of Blacks, The Harvard Crimson reported in 2021.

More than a decade removed from Gates’ arrest, the looming question is whether the latest round of reports and committees are performative or a prelude to long-awaited progress.

Knee-jerk reactions to specific incidents have previously lacked the needed staying power. The time for change in public safety protocols is long overdue, said Stephanie Guirand, a researcher for Cambridge-based The Black Response.

“People really want there to be a solution, rather than academic discourse,” she said.

Andre Luckow, BMW Group’s Head of Innovation and Emerging Technologies, is charged with exploring the potential of machine learning, quantum computing, and blockchain technology for the Munich-based automaker.

In 2018, the BMW Group co-founded what it called the Mobility Open Blockchain Initiative to coordinate activity among its 120 business partners in its supply chain. One result is BMW’s PartChain project, designed to provide traceability of components by creating more data transparency in supply chains. Another initiative is the Catena-X Automotive Network, which aims to facilitate secure data exchange between various automotive industry players.

Luckow has held several other BMW positions in IT and research since joining the company in 2005. He also teaches at the Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich and Clemson University in South Carolina.

How is BMW using blockchain technology, and why is it using it now?

I’m overseeing technology programs here, and blockchain is just one of the initiatives. One of the main drivers for enterprise blockchain … is to bridge the gap between us and our suppliers.

We attempted to cover different types of use cases. The first use case we started with was the traceability use case, and the main motivation there was [that] we don’t have enough visibility about what’s actually going on in our supply chain. [For example,] if one of our suppliers didn’t do their job. In that case, we wanted to create an ecosystem in which the participants in automotive value chain can log on and easily share data.

This system is managed by a group of people, so you have a lot of transparency and verifiability. The key environment [includes] very strict controls on who gets to see the data, and what data they get to see. Obviously, if an issue arises, we can change that.

Is the use of blockchain technology common in the auto industry?

Probably not as common as it should be. A lot of people in the auto industry are trying to figure out what we want to do…

For example, we’re working on an initiative with the German government on digital identities … Being a European company in a European state, we adhere to European values. So, privacy and digital identity are completely decentralized. There’s not a centralized registry of IDs of German citizens.

[There, blockchain] provides some benefits. For example, if you rent a car, instead of showing a plastic card, you can do an identity verification and driver’s license completely digital. It’s not only digital, you can do it in a secure way and you can do it in a privacy-preserving way.

Did you have to prove to BMW that blockchain is cost effective?

Absolutely — we do this with all our initiatives. We don’t do technology for technology’s sake. There has to be a strict purpose and business need… At the end of the day, it must yield to a business case.

Generally speaking, is the auto industry slow to adopt innovative tools?

I wouldn’t say slow; they’re just very careful. …Then, when we do something, particularly with a German company, we tend to do it to perfection.

Is it difficult to prove how valuable innovation can be?

If there’s a good idea and you have the right people and the passion to try those ideas and commit, we can always make it happen. But you always have to convince. We always find a way, and we do have success stories on blockchain. …Good ideas will survive.

Obviously, when we roll [an innovation] out to international clients, we do it on a small scale. We need to get to the state where we understand the technology and reduce the risk, until we operationalize those technologies and get to the point where the company sees the value in those technologies.

In early 2020, when Minnesota-based 3M Co. decentralized its research and development function, it drafted veteran employee Cordell Hardy to take on a new leadership role.

In early 2020, when Minnesota-based 3M Co. decentralized its research and development function, it drafted veteran employee Cordell Hardy to take on a new leadership role.

Hardy was approaching the two-decade mark with the $32 billion company; when it decentralized its model to give the presidents of its four business groups more autonomy over R&D, he became Senior Vice President of Corporate R&D Operations.

3M, which was founded in 1902, sells more than 60,000 products and operates in 70 countries. Those products range from N95 masks to orthodontic gear to the omnipresent Post-it Note. It employs about 95,000 people.

In partnership with the company’s industrial business group, R&D most recently reimagined a commercial paint sprayer with composite materials after 10 years of development. It’s faster, cleaner and lighter than conventional, all-metal models.

We spoke with Hardy about 3M’s new approach to R&D; addressing customers’ sustainability needs; and how the company tries to measure R&D impact.

…

How is your R&D group structured, and how many workers does it employ?

I manage a group called corporate R&D operations. This organization was created about two years ago as 3M transitioned to a new operating model. For a long time, we’ve had individual business units, divisions that sell different portfolios. …We’ve gone away from that structure to empowered business groups. Now, the business group presidents are in a lot more control of their organizations. In particular, the R&D units around the world reports solid line up through the division. The R&D teams for each of those business units…they all report globally up to the R&D head for each business.

That’s a massive structural change, wherein now global R&D leaders really are global R&D leaders, with team members individually in all of the major lab centers around the world. They truly do lead global organizations. … The risk is [that] we create silos where we erode the collaboration between the technical team members across business units, which has really been a hallmark of 3M’s success.

So, R&D operations was really created to serve as sort of the mortar between bricks, and to provide the range of shared technical services necessary to operate at an enterprise level within the countries where we have a scale of technical personnel and structure.

How many employees are on your team?

Our team numbers around 380 folks globally.

How many R&D workers overall, companywide?

The R&D headcount, and this is approximate, is around 10,000 folks.

You have to be thinking about how your customer or user is going to use the product, what workflow they engage in, and what their sustainability concerns may be.

What industry trends are having an influence on how your team operates?

The industry trends that are relevant to my team are the same that are relevant to the entire company. The emphasis on competitive product performance and value proposition is the same as it has always been. Customers buy first on that. However, a very strong trend — and I’m sure this is true for every manufacturer — is around lifecycle management and sustainability.

Since 2019, all 3M products have had a sustainability commitment. … Increasingly, our customers are looking for this. It’s one thing to say, “We produce this with few emissions or recycled materials.” And that’s great. But another trend is our products fitting into manufacturing processes or designs or usage patterns that increase the sustainability footprint for our customers themselves. That’s a different conversation. That means you have to be thinking about how your customer or user is going to use the product, what workflow they engage in, and what their sustainability concerns may be. That’s been a point of emphasis.

Have expectations for R&D changed at over the years, or has it been consistent?

That’s a fair question. I think there’s always the conversation around the metrics that are used to assess the productivity or the impact of R&D. 3M has invested in order of five or six percent of sales in R&D consistently, and [annual revenue is about] $30 billion. So, you’re talking about something on the order of $1.5 billion, $1.8 billion per year invested, which is significant relative to shareholder interest. There’s always a conversation about, “OK, what benefit do you get out of this investment? How do you measure it? How do you think about it? Are you positioning for the future?” That’s consistent.

The things that may be a little different are we the way we…think about what skillsets are important for our company as we go forward. Certainly, in the last 20 years, digitization has been a huge trend … so, we’ve had to think about what research and development looks like as you incorporate increasing digital content and digital technologies and capabilities and partnerships outside the enterprise and how you measure that, right? Digital business models look different and they scale differently. The ROI and the P&L itself looks different. For the businesses that we run that are heavily focused on software, they have a much different structure to their profit-and-loss than a business related to abrasives, for example.

We’ve had to think about what research and development looks like as you incorporate increasing digital content and digital technologies and capabilities.

Security architecture has recently taken center stage in the news, underscoring the role that technology and IT architecture plays in the international business ecosystem.

Fueling this trend have been cybersecurity attacks on companies, organizations and governments, which have risen sharply. One incident occurred earlier this year when a glitch in SolarWinds Inc.’s software was exploited. Other incidents have followed involving an oil pipeline operator and national food processor. These issues were even important enough to be addressed by President Joe Biden and Russia President Vladimir Putin during their summit in Switzerland over the summer.

They highlight how technology-based business planning and the global economy are inextricably linked.

The need for businesses and governments to reduce this exposure is creating greater demand for the benefits (beyond the obvious ones like value) that enterprise architecture, or EA, can provide. As such, the need for speed coupled with cost-cutting concerns has fueled the proliferation of EA software tools. And there are other changes afoot.

Steve Andriole, business technology professor at Villanova University’s School of Business, suggests that it’s also advisable to demystify the role played by enterprise architecture. He prefers the name “business technology strategy” as an alternative.

“It’s now time to strip EA down to its most basic properties – the alignment of business strategy with operational and strategic technology,” Andriole wrote in Forbes. “We can continue to complicate all this, or just admit we’re seeking business-technology alignment through the development of a dynamic business technology strategy.”

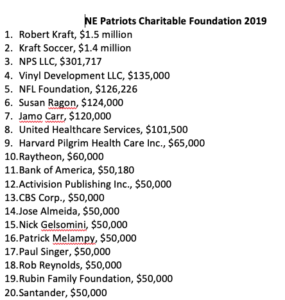

No defensive line in history could stop the Patriots’ charitable giving and publicity machine.

No defensive line in history could stop the Patriots’ charitable giving and publicity machine.

Public records show that even as the team’s owner, Robert Kraft, stood accused of paying for sex acts in Florida in 2019 (charges that have since been dropped), the New England Patriots Charitable Foundation Inc., a grant-making organization, raised $7.3 million compared with $4.5 million in 2018. That 60 percent increase came while Kraft still faced solicitation charges. Meanwhile, a US senator redirected a Kraft campaign donation elsewhere and at least one of the foundation’s grant recipients returned money, citing the principle that would be violated in accepting it.

For companies partnering with the Patriots, it was business as usual, regardless of any ethical issues in play. The charity reported receiving contributions from 155 donors in 2019 versus 151 in 2018. As appears to be a pattern, when it comes to charitable donations, Patriots vendors are carrying the ball while the Kraft family scores points with the public.

For companies partnering with the Patriots, it was business as usual, regardless of any ethical issues in play. The charity reported receiving contributions from 155 donors in 2019 versus 151 in 2018. As appears to be a pattern, when it comes to charitable donations, Patriots vendors are carrying the ball while the Kraft family scores points with the public.

Technology architecture continues to evolve much like the software and technologies it is designed to manage. And technologists are quick to note what that could mean in the future.

Technology architecture continues to evolve much like the software and technologies it is designed to manage. And technologists are quick to note what that could mean in the future.

They agree that the pressure is on for enterprise and solution architects to produce results faster and more cheaply. Meanwhile, the use of multiple clouds and AI is making the role more challenging, especially for established companies operating legacy systems. The result is a shift in focus from conceptualization and planning to faster delivery and a more pragmatic approach.

Some technologists suggest there’s now a greater demand for solutions architects than the more comprehensive approach taken by enterprise architects. Others suggest that the term “Enterprise Architecture” (EA) may be falling out of fashion. Instead, it’s now referred to as organizational design, business design, enterprise design or digital design.

Amal Alhosban, an associate professor of computer science at the University of Michigan, Flint, said chief information officers are doing more than ever. They’re now charged with understanding the business and technology architecture. They also establish information governance structures and credibility while investing in IT.

“All of these roles take more skills than ever,” she said. “Leadership roles are much broader today than before. The main reason is integrating the company’s departments under [enterprise resource planning].”

The Rise of Solutions Architecture

The demand for solutions architecture has outpaced EA and grown to become one of the more popular approaches employed by engineers compared with EA.

Unlike the broader, more holistic view of enterprise architects, solution architects target specific business problems. The resulting connection to both workflow and data flow issues have contributed to their rising popularity, according to Scott Alexander Bernard, a veteran enterprise architect and adjunct instructor at Carnegie Mellon University’s Institute for Software Research.

“People don’t see the money in enterprise architecture right now, but they do get something from solutions architecture,” he said. “People want tangible victories and my [enterprise architecture] stuff takes time.”

That’s what a small faction, not all, of corporate America believes. Recent incidents show that there’s still a willingness to go to almost any length to sanitize the truth and withhold facts from those who deserve nothing less — Americans.

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch recounted this month how chemical giant Monsanto did everything it could to discredit reporters and activists trying to expose how the company’s Roundup product was potentially connected to cancer and other health problems.

Germany-based Bayer AG, Monsanto’s parent company, acknowledged in May that it enlisted a public relations firm to target anyone who spread the word about the possible dangers of Roundup. Lives were at stake and former Reuters reporter Carey Gillam wrote about it in August.

Last year, CNN reported that Bloomberg News reassigned its banking reporter after the CEO of Wells Fargo & Co. complained about close coverage.

In July, New York-based Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, a 33-year-old watchdog group, exposed how the parent of company of Reddit and New Yorker magazine threatened this reporter who revealed a flagrant case of corporate censorship in Austin, Texas, involving Dell Technologies Inc.

Why care? Because such incidents are antithetical to American values based on the understanding that any imbalance of power is dangerous. Checks and balances are baked into our democratic system for that very reason. Remember the role reporters played in Watergate, the Catholic priest scandal, Harvey Weinstein, Theranos Inc.?

Admiral William McRaven, former chancellor of the University of Texas System, said last year, “When you undermine the people’s right to a free press and freedom of speech and expression, then you threaten the Constitution and all for which it stands.”

Reddit readers justifiably questioned whether corporate execs actually care what is reported in regional news outlets versus national publications. Although there is little hard proof, there are valid indicators that Del execs are unusually petty and thin skinned.

For example, Dell’s chief marketing officer wrote a 2014 letter to the editor after the Austin Business Journal accurately reported that Dell’s annual users conference would lack a star keynote speaker like Bill Clinton or Elon Musk in previous years.

Dell execs even take issue with tweets posted on a reporter’s personal account with direct messages sent via Twitter — after business hours. If that’s not enough, they simply deny the reporter credentials to company events.

Predictably, companies dislike censorship stories because they make it look like the companies have something to hide, which they sometimes do. Media execs don’t like such stories either because they can make them appear less than credible, which they sometimes are.

As a result, media outlets tie severance packages to non-disclosure agreements to discourage journalists from exposing incidents that fall short of the American ideals cited by McRaven. That’s notable because might certainly does not make right.

Austin deserves better; Austinites deserve the truth.